This is some dummy opening line. Just to see how the rendering of the first line of text works. So, the first line should have some more text so that it at least goes through two lines on large screens. Three lines should be an ideal.

WPF application that I am working on right now mimics the behavior of Microsoft Word 2010 when it comes to windows handling. Mimic means both from implementation and end-user and perspective. From implementation perspective, all application windows should run in the same process. (Start several “instances” of Word and take a look at Windows Task Manager or Process Explorer. You will see that they all run within the same process.) From the end-user perspective, arbitrary number of independent top level application windows can be open. Still, the user knows that they “play together” and share certain features, like dialogs. When the user opens a dialog in one of the application windows, all application windows get disabled, not only the one that called the dialog. If you are not aware of this, try it on your own. Start several “instances” of Microsoft Word 2010 and open Save As dialog in one of it. You will not be able to select some other Word instance before you close the dialog. The same goes for message boxes.

Dissecting .NET Inconsistencies

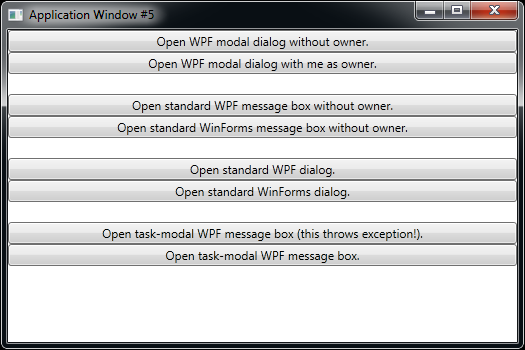

I thought that writing a WPF application that mimics the described behavior will be a trivial task. Creating a single instance application was trivial indeed. But after digging deeper into WPF dialogs and message boxes I noticed some inconsistencies in their behavior when it comes to modality. Even bigger inconsistencies become obvious if we add WinForms to the whole story. I’ve created a sample project to demonstrate these inconsistencies. Download the project and build it using the #Build.bat file. Running the A_01_OpenApplicationWindows.bat will open five application windows in the same process, each of them looking like this:

Play with the application a bit and observe on your own how each particular modal window behaves. Read the messages in the dialogs and message boxes. They contain additional interesting tips I don’t cover in this blog post.

For the impatient ones among you, here is a summary:

- WPF modal window “disables all other windows in the application”.

- WPF message box disables only its owner.

- WinForms message box disables all windows.

- Standard WPF dialog (like e.g. OpenFileDialog) disables only its owner.

- Standard WinForms dialog (like, again, OpenFileDialog) disables all windows.

Pretty messy, isn’t it?

In addition, I tried to hack WPF message box in order to make it modal for all windows. All this dialog opening reminded me of the “hello, world” sample from the Charles Petzold’s Programming Windows, 5th Edition:

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

PSTR szCmdLine, int iCmdShow)

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("Hello, Windows 98!"), TEXT ("HelloMsg"), 0) ;

return 0 ;

}

I remember me being confused years ago with that NULL at the beginning and 0 at the end of the function call. Charles explained both of them of course. Last argument is actually combination of constants that indicate buttons and icon to be displayed together with some additional options. One of the additional options is MB_TASKMODAL. According to the Win32 Programmer’s Reference, that option will make “all the top-level windows belonging to the current task disabled if the hwndOwner parameter is NULL”. Sounds exactly like what we need, doesn’t it?

WPF message box is just a thin wrapper around Win32 MessageBox(). The MessageBoxButton/Image/Options enumeration values are finally just packed into that “last argument” of the underlaying MessageBox() function. Surprisingly, MessageBoxOptions do not provide WPF equivalent of the MB_TASKMODAL constant. The same happens with the WinForms message box.

I tried to be smart and to do the following, hoping that WPF Team forgot to properly guard their message box (2000 is the hexadecimal value of the MB_TASKMODAL constant):

MessageBox.Show("Message.", "Title",

MessageBoxButton.OK, MessageBoxImage.Information,

MessageBoxResult.OK, (MessageBoxOptions)0x2000);

It didn’t work. The line above throws InvalidEnumArgumentException. However, trying the same hack with the WinForms message box went well pointing out another inconsistency in the .NET framework.

A Pragmatic Solution

Knowing all the facts listed above helped me to choose a pragmatic solution for task-modal dialogs and message boxes:

- Use WPF for modal windows. (We have to do this anyway. After all, we are developing WPF application.)

- Use WinForms for standard Windows dialogs.

- Use WinForms for message boxes.

Although I can think of a pure WPF solution it would require additional programming time. On the other side, this pragmatic approach uses existing .NET features without any additional effort. Both WinForms and WPF standard Windows dialogs and message boxes are just two different wrappers around exactly the same things. Besides, we already mix WinForms and WPF in certain parts of the application. Therefore, insisting on a pure WPF solution is not necessary.

Huston, We (Still) Have a Problem

The “without any additional effort” part of the pragmatic solution is not hundred percent true. We still have to cover one special case. To see what it is about, start the A_01_OpenApplicationWindows.bat again and open any of the dialogs which are task-modal (e.g. WPF modal dialog). Now start an additional window using A_02_OpenAdditionalApplicationWindow.bat. You can already guess, that the previously opened modal dialog will not be modal for the newly opened window.

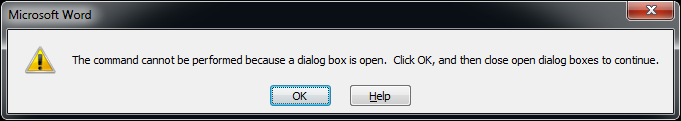

I was curious how Word covers this case. Try it on your own. Start one or more instances of Word and open Save As dialog in one of it. Now try to open an additional instance by using Windows Start Menu. The new instance will not open. The already opened modal dialog will be brought to front. However, if you try to open some existing document by double-clicking on it you will get the following message:

Is this what you actually expected? It would be interesting to see what usability experts have to say about this. But let us not open the topic of usability right now. Let’s just stick to our initial requirement - mimic the same behavior.

A simple solution is to have centralized point through which all the dialogs are open. We can then use that central point to count how many open dialogs we have (keep in mind that a modal dialog can open another one modal dialog). Centralizing the dialog handling has another long-term benefit. It will allow us to easily replace our pragmatic solution one day if eventually needed. Such replacement would then be localized and would not affect client code. Covering some additional problems in situations that we are not aware of at the moment will also be simplified if we centralize dialog handling.

The TaskModalDialogsWithSpecialHandling project contained in the sample project shows how this could be done. The TaskModalDialogHandler class represents the centralized point through which WPF dialogs and standard WinForms dialogs are open:

public static class TaskModalDialogHandler

{

private static readonly object sync = new object();

private static int numberOfOpenDialogs;

public static bool? ShowAsTaskModal(this Window dialog)

{

return ShowAsTaskModal(dialog.ShowDialog);

}

public static DialogResult ShowAsTaskModal(this CommonDialog dialog)

{

return ShowAsTaskModal(dialog.ShowDialog);

}

internal static T ShowAsTaskModal<T>(Func<T> openDialog)

{

lock(sync)

{

numberOfOpenDialogs++;

}

T result = openDialog();

lock(sync)

{

numberOfOpenDialogs--;

}

return result;

}

public static bool IsAnyModalDialogOpen

{

get { lock(sync) return numberOfOpenDialogs > 0; }

}

}

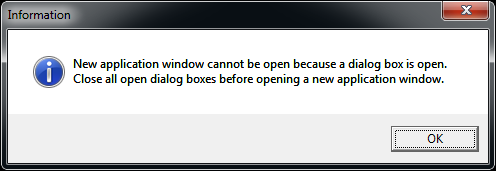

In addition, usage of the TaskModalMessageBox class (available in the same project) ensures that the message boxes will be properly displayed. Run the B_01_OpenApplicationWindows.bat and open any of the dialogs. Then run the B_02_OpenAdditionalApplicationWindow.bat in order to open an additional window. You will get the following message:

Open Questions

The pragmatic solution based on the centralized handling of modal dialogs and message boxes is a good starting point toward Word-like behavior. A few questions nevertheless remain open. They should be addressed carefully before using this approach I discussed. The questions are:

- How much effort would it be to develop pure WPF solution?

(I have one in mind. Could you think of one?) - This analysis does not cover opening of modal WinForms dialogs.

How do they behave in the whole story? Will they also automatically be task-modals? - What about legacy UI controls?

For example, what if we have some legacy OCX control that opens a dialog window? Will that dialog automatically be task-modal? How can we know at all that the dialog is currently open? - How do we enforce exclusive usage of the

TaskModalDialogHandlerclass?

Just saying to developers “You have to use this instead of callingShowDialog()directly.” is not enough. Sooner or later, someone will forget that rule and bypass theTaskModalDialogHandlerclass. How can we statically check that all dialogs and message boxes used in the application are open exclusively through the handler?