I call it my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965. At that time, I was designing the first comprehensive type system for references in an object oriented language (ALGOL W). My goal was to ensure that all use of references should be absolutely safe, with checking performed automatically by the compiler. But I couldn’t resist the temptation to put in a null reference, simply because it was so easy to implement. This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years.

Tony Hoare, QCon London 2009

Yes, null is evil. It never sleeps. It waits patiently until your concentration drops and then either hits you hard, or sneaks into your code leaving hardly noticeable bugs. The only way to fight it, at least in the C# playground, is to be constantly aware and awake. That usually means pressing F1 after calling a method or accessing a property in your code. As long as C# stays the way it is now, “Can this return null?” question can be answered only by consulting the documentation. The same applies to this question: “Can this method parameter be null?”

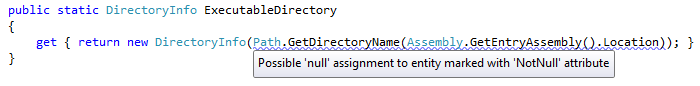

You can save some F1 keystrokes by using tools like ReSharper that will friendly warn you of the beast in the bushes waiting for its next prey:

As I will demonstrate later in this article, these friendly warnings can lead to a false sense of safety.

I Tawt I Taw a Null

By adopting null references, C# creators left us figuring out on our own if there are uninvited nulls sneaking unattended through our code. This puts us somehow in the legendary role of Tweety who tries to figure out if Silvester is somewhere around. Over the years I tried different tactics to help users of my classes and myself to immediately say “I did! I did taw a null!”. Below are three of them.

Holy Crusade

The first approach that I took went into the direction of forcing the use of XML comments in code. It was a crusade whose goal was to put the “Null is evil” comment on each and every property and method that could receive or return null. The typical output of such a crusade looked like this:

public class Test

{

/// <summary>

/// Source directory. This property is never null.

/// </summary>

public DirectoryInfo SourceDirectory { get; private set; }

public int Property { get; set; }

}

public unsafe partial ref readonly record struct Struct { }

/// <summary>

/// Source directory. This property is never null.

/// </summary>

public DirectoryInfo SourceDirectory { get; private set; }

/// <summary>

/// Destination directory. This property can be null.

/// </summary>

public DirectoryInfo DestinationDirectory { get; set; }

/// <returns>

/// Installation directory if the application is already installed;

/// otherwise null.

/// </returns>

public DirectoryInfo GetInstallationDirectory();

As you can guess, I came defeated out of each and every battle I undertook. XML comments are usually the first victim of the time pressure we often work under. Each deadline led immediately to the abrupt end of the crusade.

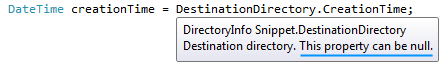

My fanatical approach also didn’t increase at all the visibility of potential null references in code. As soon as we leave Visual Studio, we cannot see any more if this line could throw NullReferenceException:

DateTime creationTime = DestinationDirectory.CreationTime;

Even when inside IDE, we still have to hover over the property with the mouse and wait a bit until the comment appears.

After few such crusades I finally laid the weapon down.

If You Can’t Beat It, Mark It

In some places I saw my colleagues were trying to mark the names of methods and properties with the “Null is evil” sign:

public DirectoryInfo SourceDirectory { get; private set; }

public DirectoryInfo DestinationDirectoryOrNull { get; set; }

public DirectoryInfo GetInstallationDirectoryOrNull()

They did increase the visibility of nulls indeed. The “Null is evil” mark sticks out and tell us immediately that something is wrong with the line below:

DateTime creationTime = DestinationDirectoryOrNull.CreationTime;

Although being a much better approach than the one I took, I somehow never liked it. The names of properties and methods looked somewhat polluted to me. In this case we are mixing semantic meaning with technical information. Yes, one can argue that the fact the method can return null is a part of its semantic. I still find the term null to be too technical for it to be in the name. It’s (not) just a matter of taste.

Let ReSharper Take Care of It

ReSharper’s Code Annotations define, among others, two attributes that improve NullReferenceException inspection: CanBeNullAttribute and NotNullAttribute. I still remember the thrill I felt after discovering them. They looked to me like that panacea I was craving for. Soon I started helping ReSharper analysis engine by providing it with additional knowledge about my code:

[NotNull]

public DirectoryInfo SourceDirectory { get; private set; }

[CanBeNull]

public DirectoryInfo DestinationDirectory { get; set; }

[CanBeNull]

public DirectoryInfo GetInstallationDirectory();

[CanBeNull]

public DirectoryInfo GetResourceDirectory([NotNull] string resourceId)

The response from the ReSharper engine was great:

I was in heaven until I realized that, yes, there are developers that actually do not use ReSharper, and, yes, there are bosses not willing paying for it.

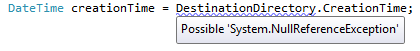

The false sense of safety that I mentioned before started to bug me. As already shown, ReSharper will point out that there is a problem in this line:

return new DirectoryInfo

(

Path.GetDirectoryName(Assembly.GetEntryAssembly().Location)

);

If we slightly change the implementation there will be no warning any more, although the Assembly.GetEntryAssembly() can return null when called from unmanaged code (an unforgettable bug which I once caused):

return new DirectoryInfo

(

Path.GetDirectoryName(Assembly.GetEntryAssembly().Location)

??

Environment.CurrentDirectory

);

Somehow I felt that I had lost the battle yet again.

Striking the Root of Evil

And so, while I was hacking at the leaves of evil; one of my colleagues, Stefan Preuer struck the root itself. Being a huge fan of C#, I somehow didn’t want to admit that the problem lies in the language itself. Null references are legal citizens in C#. On the other side, there is no built-in language concept for clearly expressing that “the value of a reference type is definitely there” or “the value of a reference type might or might not be there”. Interestingly, that concept does exist for value types. The Nullable<T> allows us to express that “the value of a value type might or might not be there”.

Stefan went beyond C# and tried to find an inspiration in functional languages.

Functional Brotherhood

Authors of functional languages like Haskell and F# didn’t repeat the billion dollar mistake. The concept of the null reference does not exist in those languages. At the same time, they offer a build in way of expressing the non-existence of an object. Haskell’s Maybe and F#’s Option types allow us to express that an object might or might not be there. Other functional languages provide similar concepts as well.

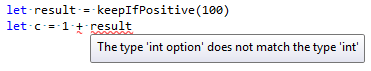

Let’s take a look at the F# option idiom as an example. The easiest way to understand it from the C# perspective is to see it as Nullable<T> for reference types. The following MSDN sample code illustrates the usage of the F# option:

let keepIfPositive (a : int) = if a > 0 then Some(a) else None

If the input parameter is positive, the method will return Some. Some represents the existence of a value. If the input parameter is zero or negative, the method will return None. None represents the non-existence of a value.

If you try to run this code snippet on TryFSharp or within the F# Interactive you will get the following output:

val keepIfPositive : a:int -> int option

The keepIfPositive() method accepts an integer as the parameter and returns an option of the type integer.

The returned value cannot be used directly in expressions where integer is normally allowed:

Here the semantics are similar to that of Nullable<T>. The underlying value has to be explicitly accessed via the Value property:

let result = keepIfPositive(100)

let c = 1 + result.Value

Accessing the value property will throw the NullRefrenceException if the option is None. Again, this is essentially the same behavior we know from the Nullable<T> type.

F# offers several ways of inspecting if there is an object behind an option or not. This is one of them:

if result.IsSome then ...

Now comes the crucial point. Yes, you can always directly access the Value property without checking up-front if the option is Some. The same is with the Nullable<T>. Nothing stops us from accessing its Value property without checking if the HasValue is true. Using the option type cannot and will not save us from the NullRefrenceException or any of its equivalents. It only forces out the beast that lies in the bushes. It’s all about increasing the visibility of possible non-existing objects in code. The check if the object exists still has to be done.

Option<T>

Microsoft.FSharp.Core.Option<T> is an example of an F# discriminated union. It can be used directly in C#, but the usage is a bit cumbersome. Although the understanding of the discriminated unions is not required in order to use it in C#, it would be fair for a C# programmer to inform himself a bit before using the F#’s Option<T> in her/his code.

On the other hand, implementing a C# equivalent of the Option<T> is rather trivial. Such equivalence can be used in a straightforward way, just like the Nullable<T>. Therefore I opted for writing my own version of Option<T> instead of using the F#’s one in my projects.

The SwissKnife.Option<T> structure demonstrates one possible implementation of the option type in C#. It is inspired by a similar structure originally written by my colleague Stefan Preuer. The Option<T> is an essential part of SwissKnife, an open source library of reusable .NET components. The SwissKnife library itself demonstrates a consistent usage of the Option<T>, according to the guidelines I will give below.

Forcing Out the Beast

As I said earlier, a possible null reference is a beast in the bushes of your code waiting for its next prey. Using the SwissKnife’s equivalent of the F# option idiom, helps force the beast out. It just simply helps. It does not solve the problem. The problem of null references lies in the C# language itself. Every attempt to solve it within the C# boundaries is just a workaround. The same applies to the Option<T>.

Still, when it comes to dealing with possible non-existing objects, in all my projects, I stick to the consistent usage of the Option<T> and the Nullable<T>. It helps the users of my classes and me of course, to clearly see that certain object, be that of reference or value type, may or may not be there. Consistent usage means following the guidelines given below. The guidelines are valid both for methods and properties. For the sake of brevity, the given examples show only how to apply them to methods.

Return Nullable<T> Instead of a Special Value Object

If a method returns a potentially non-existing object of a value type, it should return Nullable<T> of that type and not the type itself. In other words, instead of returning a special object of the type that represents non-existence the nullable without value is returned. Too often I’ve seen code similar to this one:

public int GetYearOfManufacturing() { ... }

int yearOfManufacturing = GetYearOfManufacturing();

if (yearOfManufacturing == int.MinValue)

{

// Do something in case the year of manufacturing is not known.

}

If we stick to the guidelines, the previous code snippet should look like this:

public int? GetYearOfManufacturing() { ... }

int? yearOfManufacturing = GetYearOfManufacturing();

if (!yearOfManufacturing.HasValue)

{

// Do something in case the year of manufacturing is not known.

}

Return Option<T> Instead of Null

If a method returns a potentially non-existing object of a reference type, it should return Option<T> of that type and not the type itself. In other words, instead of returning null to represent non-existence, the None option should be returned.

Again, a very familiar piece of code:

public User GetUser(string userName, string password) { ... }

User user = GetUser(userName, password);

if (user == null)

{

// Do something in case the user does not exist.

}

After applying the guideline, the code should look like this:

public Option<User> GetUser(string userName, string password) { ... }

Option<User> user = GetUser(userName, password);

if (user.IsNone)

{

// Do something in case the user does not exist.

}

The consequence of what we’ve seen so far is, if a method returns a reference type T and not the Option<T>, it automatically implies that the return value cannot be null.

Accept Option<T> as a Method Parameter Instead of Null

If a method parameter can be potentially a non-existing object of a reference type T, the parameter should be of the type Option<T> and not the T itself. The equivalent rule applies to value types and Nullable<T>.

Let us suppose that the GetUser() method, written above accepts null as a valid input, it should then be defined in the following way:

public Option<User> GetUser(Option<string> userName,

Option<string> password)

{

...

}

Here the consequence is, if a method accepts a reference type T as a parameter and not the Option<T>, it automatically implies that the parameter cannot be null. In addition, the method must throw ArgumentNullException if the argument is null.

Implicit conversion from T to Option<T>

Option<T> implements implicit conversion from T to Option<T>:

public static implicit operator Option<T> (T valueOrNull)

Null reference will be converted to None option. Any other value will be converted to Some option that represents that value.

In other words, an object of type T can be provided wherever Option<T> is required. This is especially convenient with methods that accept Option<T> as parameters. The methods can still be invoked by providing objects of type T as arguments. There is no need to “pollute” the code that invokes the method by explicitly creating options.

Instead of writing:

var user = GetUser(Option<string>.From(userName),

Option<string>.From(password));

we can simply write:

var user = GetUser(userName, password);

Convert Results of Legacy Methods to Option<T>

The guidelines listed above ensure that a library written from scratch will consistently point out every method and property that accepts or returns potentially non-existing objects. But what about the legacy code we have to use? Assembly.GetEntryAssembly() method I mentioned before is a good example. First of all, reading documentation is a must. If a method can return null, that case has to be handled properly. It’s good to point out results of such methods, by converting them to Option<T>. It’s like putting a warning sign into your code: “Hey! At the very first glance, I see that this can return null.” I find this much better than simply use the result as it is and checking it against null. Again, it’s all about increasing the visibility of potentially non-existing objects in the code.

Here is an example of such conversion that utilizes the implicit conversion from T to Option<T>:

Option<Assembly> entryAssembly = Assembly.GetEntryAssembly();

if (entryAssembly.IsNone)

{

// Do something in case of a call from unmanaged code.

}

Conclusion, If Any

The problem of null references is a problem of the C# language itself. Every “solution” within the language will be a workaround. Using Option<T> is the best workaround I stumbled across so far. So yes, it is a workaround. Just like the whole bunch of other null handling strategies that can be found out there. If you have any better solution to this problem, please suggest it in the comment box below. I’ll be glad to hear from you.