Are you ready for a nice C# riddle? It’s not an easy one ;-) so be sure to take a deep breath before jumping on it. Ready? Yes. Great! Take a good look at this line of code (thanks for taking the photo Georg!):

To avoid any misunderstandings, here is the line I am talking about:

var var = await async as async;

Now, my question to you is - is this a potentially valid line of C# code? ;-)

In other words, is it possible to write a C# program that at the same time contains the above line and compiles?

To make the question less abstract and more concrete, let’s pack the line into a bit of surrounding code:

class AwaitAsyncAsAsync

{

void CanYouMakeMeCompilable()

{

var var = await async as async;

}

}

Now we can precisely formulate the riddle. Is it possible to make the above code compileable under the following three conditions:

- It is not allowed to modify any of the existing lines of code.

- It is not allowed to delete any of the existing lines of code.

- It is only allowed to add arbitrary text in-between the existing lines of codes.

Now take a deep breath again and try to solve the riddle on your own. Take your time. You can even close this browser tab if you want. Come back once you are done to compare your approach with the solutions (yes, solutions and not a solution ;-)) given below. Keep in mind that “No, it is not possible to make that code compileable under the conditions given above.” is also a valid answer, as long as you can back it up with an argument or two.

C’mon don’t scroll down now!

I’am serious. Close this browser tab.

Don’t look at the solutions!

Give the riddle a try.

Take your time.

Think of it. Try to solve it on your own.

Think. Don’t scroll down.

Still thinking? Good.

The not so Obvious Obvious Solution

I guess you were looking for some super complex solution and missed the obvious one. I mean this one:

class AwaitAsyncAsAsync

{

void CanYouMakeMeCompilable()

{

/*

var var = await async as async;

*/

}

}

“Wait a minute! That’s cheating!”, I can hear you saying. Why? It perfectly satisfies all the three conditions and the code compiles ;-) Thus, it’s a valid solution for our riddle. Yes, we walked around the labyrinth and not through it. But the goal was to get to the other side and not to escape the room ;-)

However, my purpose for this riddle was not to teach you thinking outside of the box but rather to point out these two facts:

- Not every C# programmer is aware of C#’s contextual keywords, although he or she should be ;-)

- Writing a semantical analyzer for C# code is a tremendously difficult endeavor. Thus, getting it for free in form of Roslyn is absolutely awesome :-)

Let’s talk about the contextual keywords first.

Contextual Keywords

The riddle was originally developed for my talk on Roslyn, the C# and VB.NET Compiler-as-a-Service. Up to now, I gave that talk several times in different countries and occasions and I always asked that question - is the var var = ... line potentially compileable. The answers given on-the-fly from the numerous audiences varied from “No, it is not possible to make it compileable because a variable cannot be named var.” to “Hm, maaaybeee. It might be that some existing code already had a variable called async at the time the async keyword was introduced in C#, so…”

Most of the answers were in the first category. As far as I remember, dear talk participants correct me if I am wrong, none on of the answers ever was a clear “Yes, it is possible.”

Which tells me that the C# team didn’t do the best job possible in explaining the contextual keywords to the faithful users of the language it develops. Below is a short and simple explanation. It should be enough to grasp the idea behind C# contextual keywords. After all, they are a completely logical language feature, one of those easy to comprehend.

Let’s take the var keyword as example. What makes it contextual? The var keyword, was introduced in C# 3.0 somewhere back in 2007. At that point in time C# already existed for several years and there were already millions of lines of production code living out there in the wild. The chances were that somewhere in that haystack of code, there was a local variable or a filed or a property or a method, or… you name it named var. Not the best name for a variable, or a filed or a property or whatever, but yes, the possibility was there.

C# aims to be backward compatible. Thus, the code that potentially contained that unfortunate identifier called var still had to compile. Thus, the compiler had to distinguish between an identifier called var and the var keyword. To get a feeling for what that actually means, try to distinguish on your own which vars in the example given below are identifiers, and which are the var keyword:

int a = this.var();

var b = 0;

int var = 0;

var = this.var(var);

int.TryParse("123", out var result);

I guess it wasn’t too hard to realize that only the vars in the second and the last line represent the keyword. Other occurrences are valid C# identifiers.

In other words, var is just a regular C# identifier. Only in the context of a variable declaration, or an out variable it becomes a keyword. Thus - contextual keyword.

Long story short, this makes the

var var = ...

part perfectly valid. The same is with the async keyword. The word async is a valid C# identifier. In the matter of fact I saw it once in a code written before asyinc-await was introduced in the C# 5.0. It represented a boolean variable that was supposed to control a potentially asynchronous execution. The better name for the variable would most likely be isAsync or shouldBeAsync but that’s another story.

Back to our riddle. Equipped with the knowledge of contextual keywords, we can now formulate our first non-trivial solution.

A Non-Trivial Solution

So, the “var var =” part simply declares and initializes a variable called var. What about the right side of the assignment? Obviously, we need a variable called async and a class called async with a single requirement. In order to use await the expression:

async as async

must, of course, be awaitable. Which, after a bit of acrobatics in our mind, leads us to the following solution:

class async : Task<int>

{

public async() : base(() => 0) { }

}

class AwaitAsyncAsAsync

{

async

void CanYouMakeMeCompilable()

{

Task<Task<int>> async = null;

var var = await async as async;

}

}

The solution satisfies all the three conditions and compiles. I’ll let you figure out on your own how it works. Trust me, it’s straightforward to understand :-)

The Robert’s Solution

Robert Kurtanjek, a colleague of mine, sent me an another solution after I challenged him with the riddle. His solution is in my opinion much more elegant and based on a simple trick. Here it is:

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using async = System.Threading.Tasks.Task;

class AwaitAsyncAsAsync

{

async

void CanYouMakeMeCompilable()

{

var async = new Task<Task>(() => new Task(() => { }));

var var = await async as async;

}

}

Again, being a valid C# identifier, async can be used in the using statement as done by Robert. The compiler then figures out the rest.

Although Robert’s solution is more elegant, in my talk on Roslyn I still use the first one. Why? Because it confuses ReSharper and clearly demonstrates how difficult it is to write a bullet-proof semantic analyzer for C# code. Which brings us to the final chapter.

An Extremely Difficult Endeavor

The compiler needs to figure out semantics for these tokens based on the rules of the C# language, and if you’ve ever read the C# specification, you know that this can be an extremely difficult endeavor.

Jason Bock, .NET Development Using the Compiler API (emphasized by me)

Parsing is really really cheap comparing to semantic resolution (ask Roslyn folks).

controlflow in his comment on: ReSharper and Roslyn: Q&A

It is an extremely difficult endeavor, indeed. I was once in a team that decided to challenge that difficulty. We tried to utilize a community defined Antlr parser for C# in order to analyze C# source code and to extend the C# grammar a bit.

C# was a much simpler language at that time. The good, old version 2.0. No lambdas, no vars no async-awaits. No plenty of other language elements that poured in during the past ten years. To be frank, I wasn’t directly working on that task. (Actually, I was developing another one language from the scratch as a part of the same project.) But I was well informed about the effort behind the attempt to parse and analyze C# code on our own. And I was secretly worrying what is going to be in a month or two when C# 3.0 hits the market. Is the diligent community going to extend the Antlr parser? If yes, how quickly? Or are they just going to give up at certain point and leave us in a blind alley? (While writing this post I got curious if there are still Antlr parsers for C# available and if they cover the C# 7.2. The best thing I found after a bit of search is this parser for the C# 6.0 that apparently has some slight issues with “with deep recursion, unicode chars and preprocessor directives”.) And even if they do extend the parsers, it’s just the parser we are getting. As we will see later, the semantic analysis is where the things get really complex.

Luckily, our higher management killed the project before we were forced to face this unpleasant questions rooted in our bold decision to write a C# code analyzer on our own.

Facing the Difficulty

Still, there are those who are brave enough and skilled enough to face this extreme difficulty. The ReSharper team is a great example. Since 2004 ReSharper developers closely follow the evolution of C# and develop its own parser and analyzer in order to build an awesome product on top of them. Even now, when it appears that Roslyn made their efforts obsolete, ReSharper developers will continue to write their own C# parser and analyzer. And they have a plenty of good reasons for that. No, please do not dare to ask them (again!) if they are maybe still considering to change their mind. Here is the reaction you are going to provoke.

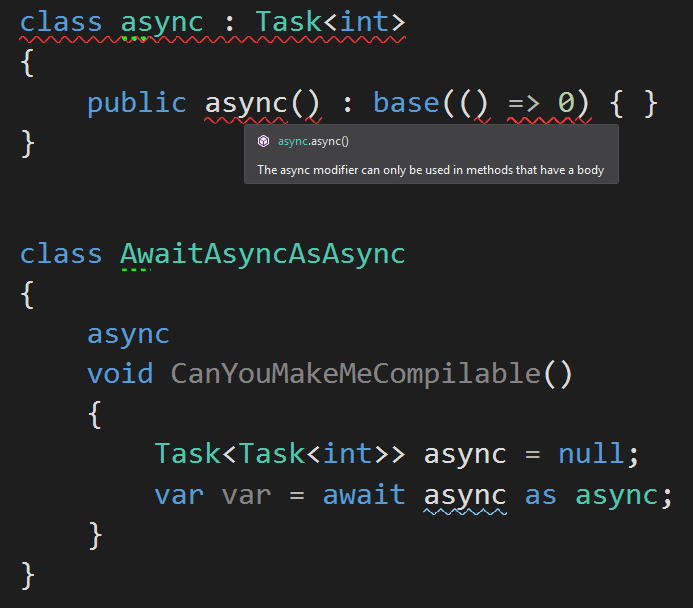

Although ReSharper is doing an awesome job in catching up with C# novelties its parser and analyzer implementation is not bullet-proof. As I mentioned before, the non-trivial solution confuses ReSharper quite a bit. You can see the output of that confusion below:

Plenty of red lines underlying a perfectly valid C# code.

I’ve never opened an official issue for this bug. Why? Because of two reasons. First, the example is fully artificial. Nobody is ever going to write such a code. Yes I know, this bug could potentially point out some places in the ReSharper parser/analyzer implementation that are worth improving, but still.

The second reason is actually the real one. It is a mixture of selfishness and educational purpose. As long as the bug is there, I can use it in my talks on Roslyn to clearly demonstrate how difficult it is to write a C# parser and analyzer on our own. Even the bests of the bests have hard time getting it 100% right.

Which pretty well underlines my personal belief that having a Compiler-as-a-Service is truly awesome. As my friend Bero once said, it gives super-powers to a regular every day C# developer.

I liked his statement so much that I called my talk on Roslyn “Super-powers and the Compiler” :-)

Let’s stop here for a while. I plan more posts on Roslyn awesomeness in the future. Meanwhile, feel free to invite me to give my talk on Roslyn at your Meetup, user group or conference :-)